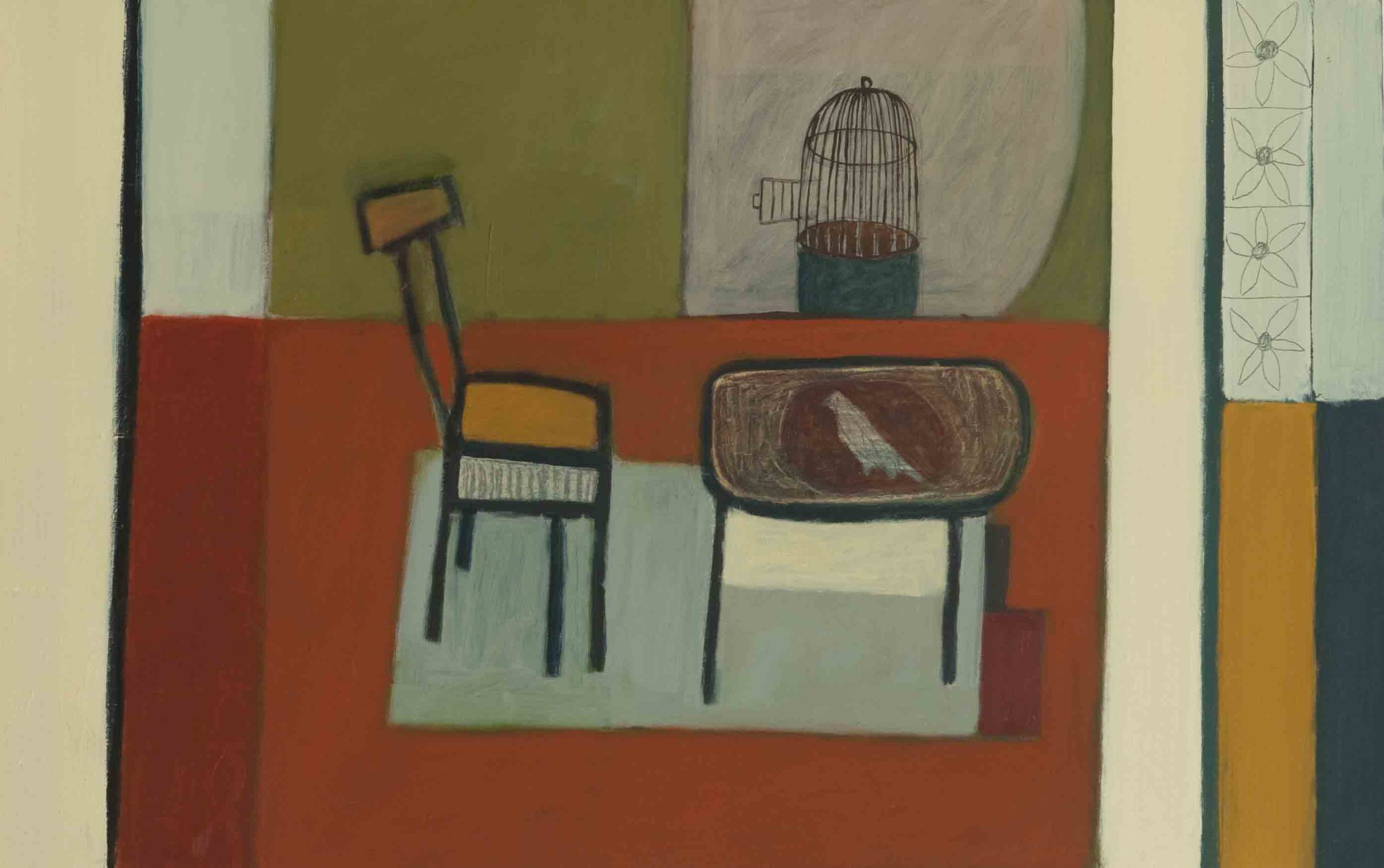

'Red Bricks and Memories 1976'

Russell Gallery, London 2012

'Red Bricks and Memories 1976'

Heath Hearn’s paintings in Red Bricks and Memories make for a remarkable blend of nostalgia and modernity. Remarkable because Hearn, in his latest collection, beautifully distills memories of his boyhood in the tight knit coal-mining town of Chesterfield in a style which is at once playful and allusive, quasi-figurative and yet, as with so much of his oeuvre, quintessentially abstract. The result is work which is fresh and invigorating: work which shows that Hearn may have journeyed into his past for inspiration, but proves that he is tireless in his quest to take the language of contemporary abstraction to a new level.

Take ‘Tin Box Toys’. Like each painting in Red Bricks and Memories, it tells a story. Shapes and forms – of plastic, of old toys, of a broken radio – are hewn from the remembered joy of a small boy’s tin box, cast here as akin to the opening of Pandora’s Box. In ‘Wash Day’, there is more by way of figuration, as a boy, sitting in a red pedal car, is greeted by a white dog. Behind, rows of red brick terraced houses are festooned with clothes hanging from washing lines. The feel is naive and yet as much as they are interconnected – many paintings echo each other – they are also wonderfully non-formulaic.

This is an artist who is determined to mine his memory in search of a new direction, rather than settle to a single motif or theme. Thus ‘Back Yard, Hot Summer’ retains a sense of the naive and utilises other artifacts of childhood as well as to the artistic language of William Scott and Alfred Wallis, both of whom Hearn cites as influences. Then there is ‘Copper, Coal and Tin’, in which a shape (of a window, or is it a chimney?) in Back Yard, Hot Summer metamorphoses into a work of pure abstraction, as muted, sombre and commanding as the mines in which Hearn’s forebears made their living.

The north was not, of course, Britain’s only mining area. The legacy of Cornish mining abounds, making for Britain’s first post-industrial landscape. Perhaps it was inevitable, then, that Hearn should make his home in Cornwall. There, in a former Napoleonic barracks high on the Rame Peninsula, he creates work which, in its merging of figuration, echoes of childhood and abstract expressionism, is poignant, thoughtful and new.

- Alex Wade is a writer and journalist. Among others, he writes for The Guardian, The Times, The Telegraph and the Times Literary Supplement.